Aortic Heart Valve 2.0

On October 29, 2024, I had my second open heart surgery to replace an artificial aortic heart valve (tissue) that was installed in 2011 (this blog was started during my recovery from that surgery). I am recovering and grateful to the medical technology that fixed me and the Abbott Northwestern/Minneapolis Heart Institute medical professionals who cared for me. I am also thankful to family and friends who helped, worried and prayed for me. Most of all, I thank my wife, Laura, my primary caregiver and, more importantly, the love of my life for over four decades.

Here is the background:(warning: some of the images below may bother some readers)

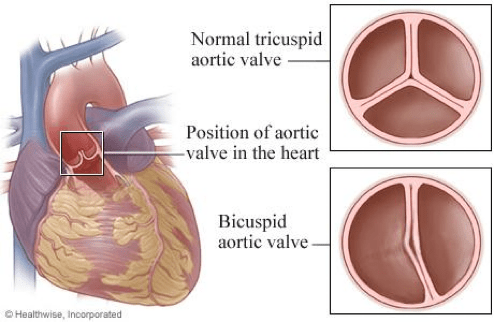

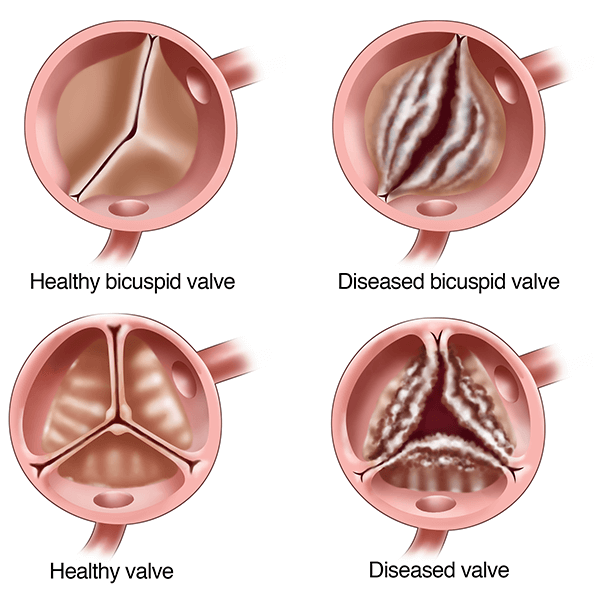

In my late 40s, I was diagnosed with a bicuspid aortic heart valve. The bicuspid valve was something I was born with and never knew was an issue until it was diagnosed. I had no cardio problems; I ran at least a marathon annually. However, as part of my annual exam, my doctor noticed that my EKG was not right and referred me to a cardiologist, who, in turn, diagnosed a bicuspid aortic valve. Once diagnosed, the plan was to check it annually via an echocardiogram and other tests. The assumption was that, at some point, the bicuspid valve would need to be replaced with an artificial valve.

Bicuspid valves are highly susceptible to stenosis (a thickening and narrowing of the valve that restricts blood flow) and/or aortic regurgitation (blood flow leaks backward into the heart due to the stenosis). This can also happen to normal tricuspid valves, but bicuspid valves are more susceptible to issues. The annual check-ups would monitor the progression of stenosis and regurgitation. Between yearly check-ups, the cardiologist said to watch for “diminished performance.” I asked, “What the heck does that mean” and he assured me that as a runner, I would notice (slower times, shortness of breath, etc.).

In the summer of 2011, I noticed “diminished performance.” I made an appointment with my cardiologist, and between a fresh echocardiogram and my symptoms, he declared it was time for surgery to replace my valve, and he hooked me up with a thoracic surgeon.

The surgeon explained my options: a mechanical or tissue valve (derived from a pig or cattle). He also noted that in addition to the bicuspid valve, I also had a weak aorta – a common genetic defect when you have a bicuspid valve. When you hear about a marathoner who dies at the finish line, it is usually because they had an undiagnosed bicuspid valve and weak aorta that ballooned and exploded (aneurysm) under the stress of the marathon. I had been lucky that never happened to me. As part of the valve replacement, he would replace the aorta with a Teflon pipe (my terminology, not his). The pros of mechanical valves are that they last a very long time. However, they require blood thinners that, in essence, make you a hemophiliac (mechanical valves also have an annoying clicking sound). A tissue valve does not require blood thinners (or any drugs to support it) and doesn’t click. However, they only had a useful life of 10-15 years, at which point you need to have it replaced. Given my active lifestyle, I decided on the tissue valve, knowing that if I lived long enough, I would likely need to replace it twice. Whether tissue or mechanical, it would be a significant surgery (crack your chest open) with a 6-week recovery.

On September 1, 2011, I had the surgery. The first few weeks were tough – recovering from having your chest cracked open was the issue, not the actual valve and aorta replacements. However, as each week passed, I felt better, and by the 6-week mark, I felt fantastic – my cardio fitness felt like I was a young man again. I could jog a mile.

Fast forward to this past summer, and I started to feel that “diminished performance” (shortness of breath) again. At the end of July, I got COVID – it was a minor case, but I developed asthma-like symptoms. At my annual cardiology appointment (September 4), it was determined that my artificial valve was showing some wear, but not significantly from prior years. There was concern that perhaps I had some arterial blockages that were causing the shortness of breath issue, so more testing was ordered. It was suggested that my asthma-like symptoms could be related to my heart. As the weeks went by, my shortness of breath got worse and worse. I also retained water (my ankles were swelled, and my stomach felt bloated). An angiogram determined that my arteries were not the issue but that my artificial valve was now quickly failing and that it would need to be replaced as soon as surgery could be scheduled. The replacement would need to be a surgical valve replacement – meaning open-heart surgery again. When I got my first valve in 2011, I had hoped that by the time I inevitably needed a new valve, I would be able to fix it with the less invasive transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) solution. Unfortunately, given my age and general good health, a TAVR was not in the cards for me – but next time (hopefully 15 years from now), I will be a TAVR candidate.

The new valve is an Edwards INSPIRIS RESILIA aortic valve. It is a bovine (cattle vs. pig) pericardial tissue valve. The beauty of new valves is they are specifically designed to be “replaced” by a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) down the line. The Edward valve is designed to have a TAVR slip inside of it.

I was initially scheduled for surgery on November 12. I met with the surgeon on October 23, 2024; she was concerned about my escalating symptoms (I was now getting shortness of breath merely walking across the room, could not lay prone, and could barely make it up a flight of stairs). She ordered a new echocardiogram to look at the state of the valve. A few days later, I got the echo, and when the surgeon saw the results, she immediately called me and said, “You are coming in tomorrow!” My valve had significantly deteriorated since the last echo in early September. This was good news to us, as we were getting pretty spooked by my quickly deteriorating condition.

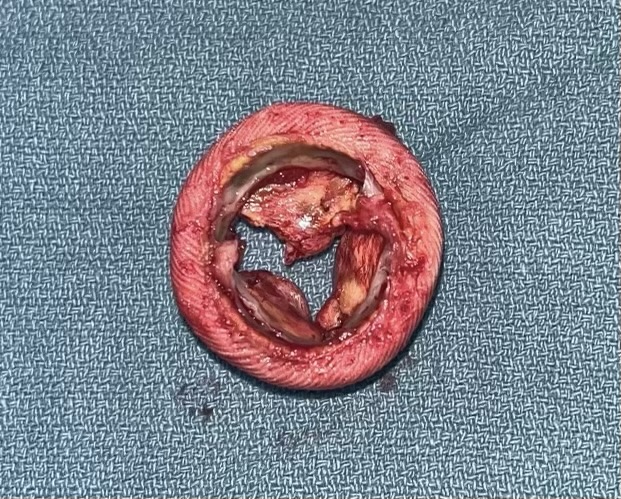

Surgery was on October 29, and sure enough, the old artificial tissue valve (which was porcine, AKA pig) was in awful condition. Below is a stock picture of what the valve looked like when it was first installed and a photo of what it looked like after removal by the surgeon. The significant gaps in the “after” photo are why I had so much trouble breathing. It turns out that the St. Jude Trifecta valve I had installed has been taken off the market as it has not performed as well as its competitors. My surgeon said I was lucky to get thirteen years out of it – most were failing at the eight-year mark.

I woke up in the ICU at about 9:00 AM on October 30 to begin my recovery. I felt about the same level of awful as I remembered from 2011. However, the next several days in the hospital were rougher than I recalled from 2011 (as a dear friend says, “A remodel is messier than new construction”). I assume that is because I was 13 years older and in a much weaker state entering surgery in 2024 compared to 2011. I had intestinal problems in reaction to drugs, and I had a couple of atrial fibrillation (Afib or AF) incidents. I was well enough to be released from the hospital in the early evening on Monday, November 4, 2024 (I was in the hospital for seven days).

As I write this post, I am two weeks past the surgery date, and I am recovering nicely. I have lost twenty pounds – primarily due to my heart condition causing me to retain water. The asthma-like symptoms have disappeared, and the water retention is fading (ankle swelling is decreasing, and stomach bloating is diminishing). My cardio is getting stronger (I can walk about a half mile, and I am getting less winded on stairs, and soon, I will start formal cardiac rehab). I have not been on narcotics since I was in the hospital – I can manage the pain with Tylenol – and the pain is a bit less as each day passes. I am on a bunch of drugs to manage potential Afib, stroke risk, water retention, blood pressure, cholesterol, etc. Hopefully, most of these drugs will not be necessary in a few months.

So, this second open heart surgery was a success. I am particularly grateful to my thoracic surgeon, Dr. Sarah Palmer, for escalating my surgery—I am not sure I would have made it to November 12, 2024 (the original surgery date). I am hopeful that I live long enough to require a third replacement valve, and that will be the less invasive TAVR solution.